A search for terms like “bug classification” or “bug priority” gives a lot of results with lots of information about how to distinguish bug severity from bug priority, methods to use to ensure that you only fix the relevant bugs, what the correct set of severities are (is it Blocker, Major, Minor, Cosmetic, or should there be a Critical in there as well?), and so on. More and more, I’m starting to think that all that is mostly rubbish, and things are actually a lot simpler. In 95% of the cases, if you have found a bug, you should fix it right then and there, without wasting any time on prioritising or classifying it. Here’s why:

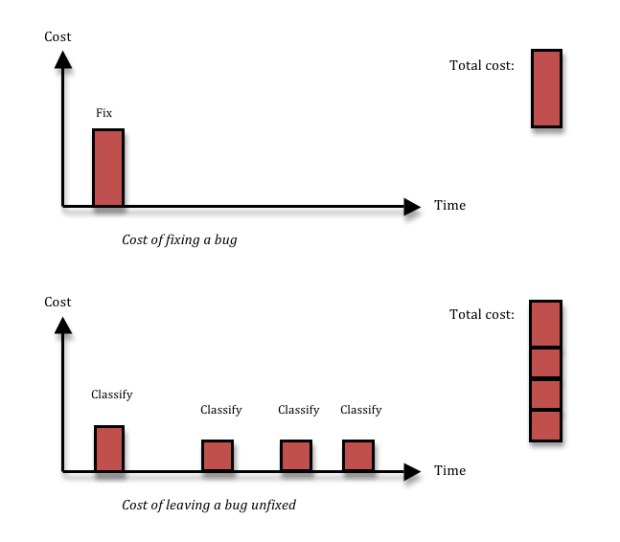

Fixing a bug means you incur a cost, and that’s the reason why people want to avoid fixing bugs that aren’t important. Cost-cutting is a great thing. The problem is, not fixing a bug also has a cost. If you decide to leave some inconsequential thing broken in your system, most likely, you’ll run into the same thing again three months down the line, by which time you’ll have forgotten that you had ever seen it before. Or, equally likely, somebody else will run into it next week. Each time somebody finds the thing again, you’ll waste a couple of hours on figuring out what it is, reporting it, classifying and prioritising it, realising it’s a dupe, and then forgetting about it again. Given enough time, that long term cost is going to be larger than the upfront fixing cost that you avoided.

What’s more, just having a process for prioritising bugs is far from free. Usually, you will want the person who does the prioritisation to be a business guy rather than a QA or development guy. Maybe the product owner, if you’re doing Scrum. That means that for every bug, she will have to stop what she is doing, switch contexts and understand the bug. She will want to understand from a developer if it is easy or hard to fix, and she will want to assess the business cost of leaving it unfixed. Then she can select a priority and add it to the queue of bugs that should be fixed. In the mean time, work on the story where the bug was found is stalled, so the QA and developer might have to context switch as well, and do some work on something else for a while – chances are the product owner won’t be available to prioritise bugs at a moment’s notice. Instead, she might be doing that once per day or even less frequently. All this leads to costly context switching, additional communication and waiting time.

The solution I advocate is simple: don’t waste time talking about bugs, just fix them. The majority of bugs can be fixed in 1-5 hours (depending of course on the quality of your code structure). Just having a bug prioritisation process will almost certainly take 1-3 man-hours per bug, since it involves many people and these people need to find the time to talk together so that they all understand enough about the problem. The cost might be even larger if you take context switching and stall times due to slow decision-making into account. And if you add the cost of having to deal with duplicate bugs over time, it’s very hard to argue that you will save anything by not fixing a bug. There are exceptions, of course. First, time is a factor; the decision not to fix will always be cost effective from a very short perspective, and always wasteful from a very long perspective. Second, the harder the bug is to fix, and the less likely it is to happen, the less likely is it that you’ll recover the up-front cost of fixing the bug by avoiding long-term costs due to the bug recurring. I think it should be up to the developer whose job it is to fix the bug to raise his hand if it looks likely to fit into the hard-to-fix-and-unlikely-to-happen category. My experience tells me that less than 5% of all bugs fit into this bucket – I just had a look at the last 40 bugs opened in my current project, and none of those belonged there. Anyway, for those bugs, you will need to make a more careful decision, so you need the cost of a prioritisation process. That means you can reduce the number of bugs you have to prioritise by a factor 20, or perhaps more. Lots less context-switching and administration in the short perspective, and lots less duplicated bug classification work in the longer perspective.

Note that the arguments I’m using are completely independent of the cost of the bug in terms of product quality. I’m just talking about development team productivity, not how end users react to the bug. I was in a discussion the other day with some former colleagues who were complaining that the people in charge of the business didn’t allow them to fix bugs. But the arguments they had been using were all in terms of product quality. That is something that (rightly, I think) tends to make business people suspicious. We as engineers want to make ‘good stuff’. Good quality code that we can be proud of. But the connection between our pride in our work and the company’s bottom line is very tenuous – not nonexistent, but weak. I want to be proud of what I do, and what’s more, I spend almost all of my time immersed in our technical solutions. This gives me a strong bias towards thinking that technical problems are important. A smart business person knows this and takes this into account when weighing any statement I make. But to me, the best argument in favour of fixing almost all bugs without a bug prioritisation process only looks at the team’s productivity. You don’t need the product quality aspect, although product quality and end-user experience is of course an additional reason to fix virtually all bugs.

So, it is true that there are cases when you want to hold off fixing a bug, or even decide to leave it in the system unfixed. But those cases are very rare. In general, if you want to be an effective software development team, don’t make it so complicated. Don’t prioritise bugs. If it’s broken, fix it. You’ll be developing stuff faster and as an added bonus, your users will get a better quality system.